Recent Articles

The Point: a Franco-American Heritage Site in Salem, Massachusetts

Traditional French Songs in Ontario

Fort William, Crossroad of a Fur Trading Empire

The Guigues Elementary School in Ottawa

Centre franco-ontarien de folklore (CFOF)

Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF)

Articles

-

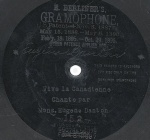

Private French-language Radio in Manitoba

Not enough attention has been paid to the struggle to develop French language radio in Manitoba and the resulting victory. Nevertheless, these efforts constitute an important and necessary step towards the preservation of French culture in Manitoba. French-language radio was an important milestone for the defence, development and affirmation of Franco-Manitoban identity. Thanks to initiatives such as this one, the French-speaking people of Manitoba were able to preserve their cultural and artistic heritage despite the daily overwhelming onslaught of English on radio.

-

Société historique de Saint-Boniface and Franco-Manitoban Heritage

The Société historique de Saint-Boniface was founded amidst considerable enthusiasm in 1902 when Monsignor Langevin, bishop of the Diocese of Saint Boniface, along with some ten companions, discovered what he believed to be the remains of Fort Saint-Charles, which had been built by the explorer Pierre Gauthier de la Vérendrye. The initial goal of the Société was to demonstrate the importance and long history of the French presence in the West by conducting archeological and historical research. The Société quickly became a centre of Franco-Manitoban intellectual life. It collected artifacts, compiled archives and published history books and pamphlets. Later it also became involved in protecting threatened francophone and Métis heritage. Beginning in the 1970s, a renewed period of intense activity led to the creation of the Centre du patrimoine (Heritage Centre), which now houses Manitoba’s francophone and Métis archives. In many respects, the Société historique de Saint-Boniface has played a critical role in promoting and preserving Franco-Manitoban heritage.

-

The Collège universitaire de Saint-Boniface in Manitoba

The Collège universitaire de Saint-Boniface is the oldest post-secondary educational institution in Western Canada. It is located in what is today the heart of Manitoba Francophonie. Its student body, numbering about a thousand, includes francophone students from Manitoba, Québec and the Western provinces, anglophone immersion students, and students from French-speaking countries around the world (West African countries, France, and French overseas territories). The dome of the main building is a cultural landmark and a symbol of the long struggle for French-language education in Manitoba. This article presents the history of this institution, with special attention to the main stages of development since its humble origins in 1818.

-

The French Language in Manitoba: French-Canadian and European Roots

According to the 2006 census, Manitoba residents whose mother tongue is French account for slightly less than 4% of the province’s overall population. The history of the French language spoken in Manitoba, surviving through stubbornness and a wilful activism for the conservation of its cultural and linguistic particularities, nonetheless bears the imprint of the rich and varied origins out of which it has grown. The varieties of French used by the French-speaking community in Manitoba still bear the marks of their linguistic forebears—regional varieties of French brought to Manitoba by settlers who had come from Quebec or from French-speaking Europe in the early years of the 20th century.

-

Assomption Sash

The Assomption (or arrow) sash is a symbolic piece of clothing central to the culture of the French-speaking population of North America. The item was widely worn for almost a century, from the end of the 18th to the end of the 19th century, before it fell into disuse, a result of the decline of the fur trade industry. Subsequently, this "masterpiece of Canadian domestic textile industry", as E.-Z. Massicotte once put it, came to be associated with the traditional cultures of the French-Canadian and the Métis. Today, enthusiasts have committed themselves to safeguarding of this cultural custom. Thanks to artisans who continue to weave sashes according to traditional methods, this unique technique has been kept alive.

-

Canada Day

Celebrated on the first of July, Canada Day (or Dominion Day as it was officially known until 1982) commemorates the Canadian Confederation of 1867. In 1958, the federal government of John Diefenbaker began the tradition of hosting official celebrations in Ottawa, combining both formal and festive components, to commemorate the founding date of the country. The nature of the celebrations held in the National Capital Region have changed over time to reflect changing conceptions of Canada's national identity. Grouping together performers from across the country, these celebrations, taken together, present an evolving conception of the linguistic and cultural heritage of Canada.

-

Champlain’s astrolabe: the journey of a mythical Canadian heritage object

An astrolabe that may have belonged to the explorer Samuel de Champlain was discovered in 1867 near the Ottawa River. More than a century later, this precision instrument known as "Champlain's astrolabe" has become one of Canada's most highly prized heritage objects and it now belongs to the permanent collection of the Canadian Museum of Civilization. The unique journey of this iconic object of Canadian history resembles a fictional tale, with first Champlain as the central figure, and then the astrolabe. We invite you to discover how this 17th century navigation instrument became a Canadian heritage symbol.

-

College Saint Jean of Alberta

In 1997, Alberta's Collège Saint-Jean received the Prix du 3-juilet-1608 from the Conseil de la Langue Française [Council for the French Language], the Quebec government's French-language enrichment (and conservation) agency. This award recognized the important contribution made by the college in promoting French language and culture in North America, as well as the key role it played (and continues to play) within the Franco-Albertan community. For close to 100 years, Alberta's French speakers have benefitted from the vitality and influence of this institution, which is now recognized throughout Canada for its quality post-secondary education programs, and indeed around the world for its research activities.

-

Community Governance of the Francophone Minority: a Cultural Heritage

As a whole, the francophone minority in Canada has survived and is developing thanks to a constant investment in what could be called community governance, that is, the forms of organization that it has adopted in order to form a group and to influence public authorities. Governance of the francophone minority, now woven throughout the fabric of the country, was formed gradually to protect against the attacks of an often-hostile majority. By its persistence and its resilience, this governance is rich in lessons learned and is an integral part of French cultural heritage in North America.

-

Floral Beadwork: A Métis Cultural Heritage to Rediscover

In the late 18th century, Métis women from the Great Lakes and Red River area of Manitoba sewed moccasins, tobacco pouches, saddles, gloves and clothes decorated with bright colourful beads and silks that caught the eye of travelers. These imaginative women would develop a distinctive floral design that would become the most widely used style among the Métis throughout the 19th century. Natives referred to them as the "Flower Beadwork People" because of this style. In developing this trademark style, the Métis women have given Canadians a piece of unique cultural heritage. Although this art has long been forgotten and most still know very little about it today, there remain a few collections in museums that display some of these hand worked items, namely the James Carnegie Collection(9th Earl of Southesk), which is on display at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton. As they once did in the past, the Métis women of today still create and sell clothing and objects. It allows them to gain more economic independence within the community and enables them to better support their families.

-

Fransaskois Music and Song

In 2006, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Town of Gravelbourg, the a cappella group Octopus released its first compact disc…after 43 years of existence! Formed in 1963 at College Mathieu by Father Fernand Binette OMI, this Fransaskois group would undergo many changes and enjoy much success over the years. Its long existence, in close association with College Mathieu in Gravelbourg, is part of the history of French-language song in Saskatchewan. Singing has always played an important part in Fransaskois cultural life; it has been a means of expression, a reason for getting together, and a source of identity. Singing took several different forms over the 20th century: patriotic songs, festivals, boîtes à chansons, choral singing, and the emergence of Canadian stars like Hart Rouge. Today, while economic problems clearly exist, French-language music is still very much alive in the Fransaskois community.

-

French Prairie, Oregon

French Prairie, located in western Oregon’s Willamette Valley, takes its name from the bi-cultural French Canadian and Indian families who colonized the area in the 1820s and 1830s These French-Indian settlers served as important historical actors in Euro-American colonization of the region, which began with the overland fur trade in the 1810s. French Prairie was originally the home of the Ahantchuyuk Kalapuyans, an aboriginal people whose numbers declined precipitously during 1830s and 1840s as a result of disease and Euro-American emigration. The Willamette Valley later become the primary destination of the American Oregon Trail settlers of the 1840s. Following the eventual assimilation of the French-Indian families and the political ascendancy of the Anglo-Americans, the historical role of the francophones was often obscured in traditional texts on Oregon history. However, the history and heritage of the francophone settlers remained in the memories of their descendants. Today twenty-first century visitors to Champoeg State Heritage Area have opportunities to learn about the French-Indian settlers of French Prairie.

-

Gabriel Dumont, the Last of Great Métis Leaders

North America's Métis nation was born out of the meeting of the First Nations and European settlers between the 17th and the 18th centuries. Gabriel Dumont, along with his friend Louis Riel, are emblematic figures for this unique people group. He took up arms to fight for their rights at the battle of Batoche in 1885. He also spoke for them in New England and in Quebec, where, in 1888, he sought to present the French Canadian Métis as the civilisers of the Prairies. Even today, his leadership skills, his loyalty, his ability to make decisions and his exceptional determination are an inspiration to the many Métis community organisations in Canada and the United-States. Gabriel Dumont's actions have helped give the Métis people their rightful place at the heart of French cultural heritage of North America.

-

Gabrielle Roy House

On November 23, 2001, the St. Boniface home, where Gabrielle Roy was born in 1909 and where she lived until 1937, was designated a "Historical House" by the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba. Gabrielle Roy, the most famous Franco-Manitoban writer, whose works have been translated into and published in more than 14 languages, belongs to an elite group of French language authors from around the globe. In 1947, she became the first Canadian writer to receive the Femina prize, awarded in France, for her novel Bonheur d'Occasion [known in English as The Tin Flute]. The official opening of the restored St. Boniface home, where she was born, took place on June 19, 2003, after the long process of preserving and restoring it. Since then, the house has served as a museum, which includes an interpretation and exposition centre that presents the life of Gabrielle Roy and her family.

-

Henri-Gustave Joly and the Development of our Natural Heritage

Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière was a multifaceted man: an honest politician, a wise businessman, a passionate tree-grower and an influential figure in Canada's linguistic duality in the 19th century. He came from an important New France family, but was born and educated in France, and he went on to make his mark on the political scene in Quebec, British Columbia and Canada. Because of his passion for horticulture and for trees, he was a promoter of forest conservation and he created a huge romantic garden-park, which has been restored in recent years and which is still recognized today for its beauty and the rare species it contains. He is remembered as an affable and scrupulously honest man, a champion of tolerance, and a visionary in the areas of agricultural progress and forest conservation.

-

Historical Reenactment: A Fascinating Hobby

Historical reenactment, a relatively recent pastime, allows participants to immerse themselves to varying degrees in a specific historical period or event in order to experience what everyday life was like at that time (food, clothing, traditional crafts and skills, etc.). It is hard to imagine a more intimate form of contact with the past, because reenactment not only provides an opportunity to learn about history, but to feel it too. In North America and in Europe, various attempts have been made to clarify the definition of reenactment. Here is another contribution.

-

La Vérendrye: Archetypal Ideal of the Voyageur

La Vérendrye is one of the key explorers who left his mark on the history of New France. He remains one of the great emblematic figures of Western Canada, largely due to the fact that he was the first voyageur to reach the region of present-day Winnipeg. In Manitoba, his memory is especially honoured and celebrated in commemorative festivities, cultural events and the arts. These celebrations highlight the fact that the French have been present on the Prairies since the days of the Discoverers. In the eyes of many, La Vérendrye epitomizes the archetypal voyageur. He is a symbol of courage and the spirit of adventure, qualities deeply rooted in the mentality of the French, Métis and English voyageurs, who gradually settled this part of North America.

-

Lac Sainte-Anne: A Franco-Amerindian Place of Pilgrimage

On July 24th, 1991, Douglas Crosby, president of the Oblate Conference of Canada, chose the sacred shores of Lac Sainte-Anne to present, on behalf of 1200 oblates, his official apology to the First Nations of Canada for the negative effect that the time spent in residential schools had on aboriginal peoples. His choice of location was no coincidence, for in native spiritual tradition, Lac Sainte-Anne is a place of great importance. Furthermore, it is also an important landmark in the history of Franco-Indian relations in Western Canada. Located approximately sixty kilometres northwest of Edmonton in the heart of Alberta, Lac Sainte-Anne was an ancestral gathering place. Since 1889, native peoples (Cree, Dené, Black-Foot and Métis) have come to the lake to celebrate Sainte Anne's Day. Every year in July, between 35,000 and 40,000 pilgrims from Canada and the United States gather on the lakeshore. On July 19th, 2007, Parks Canada and the Historical Sites and Monuments Board of Canada unveiled a plaque commemorating the historical importance of this gathering place.

-

Maillardville, a francophone community in British Columbia

For more than two centuries, French-speaking people have been in British Columbia. Francophone members of the Mackenzie and Fraser expeditions crossed the Rockies on the way to the Pacific. Later, voyageurs working in the fur trade settled in various parts of the province over the course of the nineteenth century. From 1909 on, the Maillardville community has been an example of the role played by French Canadians in development of the province. Several hundred of them came to British Columbia, recruited to work in a sawmill on the banks of the Fraser River east of Vancouver. At that time, Fraser Mills was a small company town surrounded by forest. Within a few years, a village including a church, a convent, a school, a post office, a police and fire station, and a number of businesses had replaced the dense forest north of the sawmill. The francophone village of Maillardville was born, and would go through many changes over the decades.

-

Métis Fiddling and Dance

Métis peoples are those of mixed French and Native ancestry, often including other cultural origins as well, especially Scottish. The word came into common use in the 1800s on the Canadian prairies to describe the children of French-Canadian traders and First Nations women, largely Cree and Ojibwa. These intermarriages spawned a syncretic culture, including distinctive languages, called Mitchif, or Métchif, as well as clothing, food, and music. Central to Métis musical culture, both past and present, is a fiddle and dance tradition which reflects Scottish, French and Aboriginal roots as well as other influences. Fiddling has been so identified with Métis culture that Turtle Mountain players say, “There’s no Metchif without no fiddle. The dancin’ and the fiddle and the Metchif, they’re all the same”(NOTE 1).

-

Métis Trails of Western Canada

On the 17th of February 1997, a plaque was unveiled atthe Alberta Legislature in Edmonton. Simultaneously, the same event was being commemorated at the Fort Garry Hotel in Winnipeg. Members of the Métis Nationof Alberta and Manitoba as well as representatives of the Ministry of CanadianHeritage and local historic associations came together on that day ofcelebration. No monument was inaugurated and no tribute was paid to any personin particular. Instead, these representatives were gathered to underline thenational historical importance of the Carlton Trail, a transportation routethat marked the development of the Northwest during the 19th century.

-

Quebec Beer, Brewers and Breweries

Beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage in Canada and Quebec. Beer drinking as a tradition dates back to the days of New France, making brewing one of the oldest trades practiced in the Lawrence Valley. However, both brewing practices and the popularity of beer underwent significant changes, as the British tradition began to have a strong influence on the beer industry through the establishment of the first large-scale modern-day brewery, the Molson Brewing Company. The Industrial Revolution made it possible for beer to become a mass-produced commodity, brewed and bottled in factories and distributed by increasingly sophisticated infrastructures. Nowadays, microbreweries have revived the practices of artisanal brewing, as a number of festivals celebrate the many varieties of this ancient beverage.

-

Red River Cart

The French Canadian traders and the Métis developed a wide network of trading routes across the Prairies using routes that were based on the Indian trails, which often followed buffalo trails. Crucial to the expansion of these trade routes, Métis craftsman of Red River settlements created a unique cart: the Red river cart. This cart is the best-known symbol of Métis culture. It is a symbol of the ingenuity, their nomadic way of life, and their trade skills that contributed in the development of the Prairies economy. Carts are still being made today by the Red River Metis Heritage Group at St. Norbert, Manitoba.

-

René Richard, Landscape Painter

René Richard (1895–1982) is remembered as a remarkable and charming man who followed his passions. He spent the first half of his life in search of himself, surviving in the wilderness in harsh conditions. Richard’s father had emigrated from Switzerland to settle in Alberta, but Richard chose a nomadic existence among the Cree and Inuit in Canada’s North. All alone in these wide empty spaces, Richard became an artist. In 1927, he decided to study painting in Paris, where he met Canadian painter Clarence Gagnon. Upon his return to Canada in 1930, he again took up trapping, this time in Manitoba, before finally settling in Baie-Saint-Paul where he spent the rest of his life, painting the luminous, brightly-coloured landscapes of the Charlevoix region in a style halfway between traditional figurative painting and the emerging Quebec expressionism of the 1950s. Richard’s work shines a light on many aspects of Canada’s natural landscape and social history and represents a major contribution to Canadian art.

-

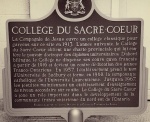

Sacred Heart College, Sudbury

An Ontario Heritage Trust plaque at the corner of Notre-Dame and Kathleen streets in Sudbury marks the location of Sacred Heart College. Thousands of students passed through the college doors over the years, with many going on to become leaders who left their mark on the Franco-Ontarian community and beyond. The English plaque reads as follows: “The Society of Jesus opened a classical college at this site in 1913. The next year the province granted Sacred Heart College a charter giving it degree-granting powers. At first the college was bilingual, but after 1916 it taught exclusively in French. Sacred Heart College became a centre for the education and formation of young Franco-Ontarian men. In 1957, it changed its name to the University of Sudbury, which became the Catholic component of Laurentian University in 1960.” Sacred Heart College played a crucial role in the flowering of French Ontario’s collective identity and memory. It was here that Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario (SHNO) was founded in 1942. Today, this important heritage organization keeps local history alive with its archival collection, conferences and publications.

-

Saving the American White Pine

The white pine, often described as a majestic tree of extraordinary size, has fascinated and inspired naturalists and artists for generations. With a height of more than 40 m and a trunk diameter often more than 100 cm, it is the giant of northeastern North American forests. In the right conditions, the white pine is fast-growing and surprisingly long-lived. Some trees alive now witnessed the arrival of European explorers of the early seventeenth century. Of the millions of hectares of pine forests that covered eastern North America 400 years ago, only a few remain, between 0.25 and 5% according to various authors. These scattered forests, changed and weakened, depend today on the care that owners and governments are willing to provide. What is being done to ensure the survival of this precious natural heritage?

-

The Cathedrals of Saint-Boniface

Since 1818, six churches have stood in succession in Saint-Boniface, Manitoba testifying to the longstanding French and Catholic presence in western Canada. The Red River town—now a borough of Winnipeg— grew by leaps and bounds over its first fifty years, from the humble Saint-Boniface Mission to the seat of a vast archdiocese covering most of western Canada. This growth led to the successive construction of five cathedrals. The largest and most prestigious, completed in 1908 under second Archbishop Adélard Langevin, was destroyed by fire in 1968, to the dismay of the francophone population for whom it was a symbol of strength. Today’s cathedral, consecrated in 1972, stands within the great edifice’s ruins, preserving the heritage value of a site that strongly symbolizes the francophone presence in western Canada.

-

The Cercle Molière: for the Love of Theatre in French

Every year without fail, since 1925, the Cercle Molière [Molière Circle] has presented theatre in French in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The Circle is recognized as Canada's oldest theatre company of any language and represents one of the finest French culture treasures that has roots in Western Canada. Originally operated by passionate amateur theatre lovers, the Circle is now a professional company. It offers a program for adults and another for younger audiences, as well as providing training sessions in the dramatic arts. The Circle is a major monument to local heritage and is a key player on Manitoba's French-language arts and culture scene. It has always been a rallying point for the energies of the Franco-Manitoban community, which has often helped it overcome the many obstacles that it has had to face.

-

The Heritage of Métis Language in Western Canada

The second half of the 18th century saw the emergence of two distinct communities in the fur trade territories known as the Pays d’en haut: the French-speaking Métis and the English-speaking Métis known as “halfbreeds.” Both communities were born of the unions of aboriginal women and white men. The French or English that Métis children learned from their fathers evolved over time to give rise to two local dialects: French Michif and Bungee, a vernacular form of English. But these children had also learned their mother’s aboriginal languages. They would create a whole new language, Michif, a remarkable blend of French, Cree and Ojibwa. Today, this remarkable linguistic heritage is threatened with extinction.

-

Wayside Crosses

Nearly3,000 wayside crosses are still standing along the highways and byways of theProvince of Quebec. They representa precious heritage-a legacy of the past. The first crosses were erected by Jacques Cartier as a symbol ofterritorial appropriation. Later,the pioneers used them to mark the founding of a village and French Canadianpeasant farmers (then known as habitants) did thesame upon staking their land claims. All sorts of reasons have led French Canadians to put up waysidecrosses: farmers set them up closeto their fields for divine protection; parish priests erected them to indicatethe site of a future church; parishioners raised them up on the halfway pointalong a concession or range road, where they would gather for the eveningprayer. Although wayside crossesare first and foremost religious objects, over time they have taken on a moreheritage-oriented significance, their distinctive outline characterising aparticularity of the Quebec countryside that has come to be associated with thefaith of the French Canadian forefathers.

Images

-

Letitia Bird, métisse

crie, Rivière-...Article :

Floral Beadwork: A Métis Cultural Heritage to Rediscover -

Wigwam, un Métis oji

bway, Manitoba,...Article :

Floral Beadwork: A Métis Cultural Heritage to Rediscover -

Saint-Boniface (Manit

oba) : funérai... -

Saint-Boniface (Manit

oba) : groupe d...

-

Habitations de colons

et charrette d...Article :

Red River Cart -

Habitations de colons

et charrette d...Article :

Red River Cart -

Collège des Jésuite

s à Saint-Boni... -

Colonie de la rivièr

e Rouge à Sain...

-

Plan de la ville de S

aint-Boniface, ... -

Compagnie_La_Ve__rend

rye_Manitoba.jp... -

Foyer Notre-Dame (pou

r personnes âgé... -

Campement métis dans

la prairie, Man...

-

Le costume officiel d

u club de raque... -

Carte de la présence

métisse au Mani... -

Carte de la répartiti

on du Bungee au... -

Lac Manitoba

-

Ancien couvent des So

eurs Grises à W... -

Plaque commémorative

du Couvent des ... -

Annonce publicitaire

pour des terres... -

Carte de Réal Bérar

d intitulée « ...

-

Carte montrant les mu

nicipalités bil... -

Charles-Agapit Beaudr

y, prêtre-colo... -

Couverture de l'ouvra

ge de Jacquelin... -

Entrefilet paru en pa

ge couverture d...

-

Entrefilet paru en pa

ge couverture d... -

La chanteuse d'origin

e franco-manito... -

La quartier francais

de Saint Bonifa... -

Le drapeau franco-man

itobain

-

Le personnel du burea

u d’immigration... -

Logo de la Société

franco-manitoba... -

Ouvrage Le Nord-ouest

: la province ... -

Page couverture d'un

guide pour l'é...

-

Page couverture du Co

lonisateur cana... -

Photo d'enfants assis

sur un char lo... -

Photo d'un groupe d'h

ommes suisses d... -

Photographie du cénot

aphe (Piroiton)...

-

Population du Manitob

a selon la lang... -

Retour de la messe de

minuit au Mani... -

Scènes de la vie ré

elle au Manitob... -

Autre monument érigé

à la mémoire de...

-

Pierre tombale de Lou

is Riel devant ... -

Saint-Boniface de l'a

utre coté de la... -

Tombe de Louis Riel d

ans le cimetièr... -

Dancers, Friendship C

entre, Dauphin,...Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance

-

Dancers, Friendship C

entre, Dauphin,...Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

Dancers, Friendship C

entre, Dauphin,...Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

Eldon Campbell, Kines

ota, Manitoba.Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

Grandy Fagnan, Camper

ville, Manitoba...Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance

-

Carte montrant la rou

te reliant le l...Article :

Métis Trails of Western Canada -

Détail d'une carte mo

ntrant la route...Article :

Métis Trails of Western Canada -

Méandres dans la rivi

ère Rouge près ...Article :

Métis Trails of Western Canada -

Plaque commémorative

de la Commissio...

-

10e anniversaire de C

KSB, le premier... -

Bureaux administratif

s de Radio-Sain... -

Louis Leprohon, géran

t de CKSB de 19... -

M. l'abbé Antoine Des

chambault, memb...

Vidéos

-

De la rivière Rouge à Batoche en charrette métisse

Ce film suit le périple d’un groupe de Métis parti de rivière Rouge, au Manitoba, jusqu’à Batoche, en Saskatchewan, en utilisant la traditionnelle charrette de la rivière Rouge pour commémorer les chemins parcourus par leurs ancêtres et l’importance de cette démarche pour l’identité métisse. En traversant des forêts, des rivières et des routes, ces gens font l’expérience des difficultés rencontrées par les voyageurs métis pour pratiquer la chasse et le commerce. Lors de leur passage dans quelques villages, des célébrations ont lieu à la mémoire de leurs ancêtres. Cette randonnée en charrette fait découvrir l’importance de l’histoire, des traditions et de la famille pour la communauté métisse. Durée: 6 min. 24 sec.

-

Le Cercle Molière

Ce documentaire sur l’histoire et les réalisation du Cercle Molière présente des extraits de pièces produites par le Cercle de Molière démontrant la diversité des sujets explorés par les dramaturges et les acteurs. La formation donnée par cette seule troupe de théâtre francophone au Manitoba est essentielles pour assurer la relève. On présente aussi les différents metteurs en scène qui ont participé à la mise en place de la première troupe de théâtre au Canada, le Cercle Molière, et à l’essor du théâtre professionnel dans la communauté francophone manitobaine. Durée du Vidéo: 7 minutes 29 secondes.

Article :

The Cercle Molière: for the Love of Theatre in French -

De la rivière Rouge à Batoche en charrette métisse

Ce film suit le périple d’un groupe de Métis parti de rivière Rouge, au Manitoba, jusqu’à Batoche, en Saskatchewan, en utilisant la traditionnelle charrette de la rivière Rouge pour commémorer les chemins parcourus par leurs ancêtres et l’importance de cette démarche pour l’identité métisse. En traversant des forêts, des rivières et des routes, ces gens font l’expérience des difficultés rencontrées par les voyageurs métis pour pratiquer la chasse et le commerce. Lors de leur passage dans quelques villages, des célébrations ont lieu à la mémoire de leurs ancêtres. Cette randonnée en charrette fait découvrir l’importance de l’histoire, des traditions et de la famille pour la communauté métisse. Durée: 6 min. 24 sec.

Article :

Métis Trails of Western Canada Red River Cart -

Musée de Saint-Boniface

Philippe Mailhot, directeur du Musée de Saint-Boniface, parle de la vocation et de la mission de son institution située dans l'ancien couvent des Sœurs Grises de Saint-Boniface, construit entre 1845 et 1851, reconnu lieu historique national. Au gré de sa présentation, nous découvrons l'architecture du bâtiment et les expositions présentées à l'intérieur. On voit notamment de nombreux artéfacts illustrant la vie des Métis et de leur chef Louis Riel, ou le quotidien des colons canadiens-français, ou encore le mode de vie bourgeois du début du XXe siècle au Manitoba. Autant d'occasion de mettre en valeur le riche patrimoine de la province.

Documents sonores

-

C Reel - Hyacinth Mckay, Pine Creek Manitoba. Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba

C Reel - Hyacinth Mckay, Pine Creek Manitoba. Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba

Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

D Reel

Interprète : Emile Spence, Eddystone, Manitoba. De l'album Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba Durée : 1 minute 14 secondes

Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

D Reel

Interprète : Fred Mckay, Pine Creek, Manitoba. De l'album Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba Durée : 1 minute 41 secondes

Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

Drops of Brandy

Interprète : Walter Flett, Bacon Ridge, Manitoba. De l'album Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba Durée : 1 minute 57 secondes

Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

G Jig

Interprète : Albert Beaulieu, Ebb and Flow, Manitoba. De l'album Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba Durée : 1 minute 14 secondes

Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

Quadrille Set

Interprète : Willie Mousseau, Ebb and Flow, Manitoba. De l'album Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba Durée : 3 minutes 45 secondes

Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance -

The Devil's Reel

Interprète : Grandy Fagnan, Camperville Manitoba. De l'album Old Native And Metis Fiddling In Western Manitoba Durée : 3 minutes 35 secondes

Article :

Métis Fiddling and Dance