The Château Ramezay Museum, Montreal

par Fournier, Martin

The prestigious family residence built in 1705 by Claude de Ramezay, governor of Montreal, today houses a historical museum, the Château Ramezay Museum, across from City Hall in the heart of Old Montreal. This building is one of the few from the French regime that remain in the city. The Château Ramezay Museum, opened in 1895, is thus the first Quebec museum devoted to history. The building was also the first to be classified as a historical monument by the Commission des monuments historiques de la province de Québec in 1929. The unique story of this three-hundred-year-old residence is an excellent illustration of how the role played by heritage has changed in the society of Quebec and of Canada.

Article disponible en français : Musée du château Ramezay à Montréal

Revealing history and heritage

By turns family home of Claude de Ramezay, second home of the intendants of New France, office of the English governors of Lower Canada, faculty of medicine of Laval University in Montreal, then historical museum, the Château Ramezay today receives 50,000 visitors a year on average. This building is a prime symbol of the French origins of the city of Montreal, by the age of its construction going back to the French regime, by its architectural style, by objects displayed there, and by the recently established formal French-style garden. It also embodies the British influences that have marked Montreal and the province of Quebec, by the process of creating the museum, the origins of part of its collection, and the people who have established an exceptionally valuable heritage. Finally, by its multicultural programming reflecting the cosmopolitan reality of Montreal today, this institution offers a true panorama of Quebec history.

A growing interest in heritage

During the nineteenth century, interest in history grew rapidly in Europe and the United States. Canada was no exception to the rule, with the development of learned societies made up of well-off, educated people – particularly in Montreal – concerned with history and culture. The members of these associations, with various interests and passions, met regularly and exchanged ideas with each other and with correspondents from other countries. On their travels they discovered currents of thought and examples that stimulated their interest and commitment. In 1862 two Montreal learned societies, one francophone and one anglophone, joined together to create the Numismatic Society of Montreal. Soon afterwards, this society recruited new members and widened its scope to become the Numismatic and Archaeological Society of Montreal.

At that time numismatics - the study of coins and medals - played an important role in commemorating and bearing faithful witness to history. Some members of this new Society also took part in archaeological digs to bring to light traces of the past. The Society’s aim was to ensure that important events, places and people were recorded in the memory of the public. Its members placed memorial plaques, collected old objects, and bought books on history, science and culture. In 1892 they organized a large exhibit for Montreal’s 250th anniversary, and participated in erecting a statue of the city’s founder, Sieur Chomedey de Maisonneuve. Society members were very conscious of the need to save “authentic” objects from the French period of Montreal’s history. For this reason they were soon fully involved in the fight to save this illustrious building from destruction.

History of the building

In 1705 Claude de Ramezay, who had been appointed governor of Montreal (NOTE 1) the year before, built a residence that can certainly be described as opulent, in a modest colony such as New France was at the time. It was made of fieldstone, with three floors including the vaulted cellar and the attic, and was 60 feet long by 36 feet wide (18 metres by 11 metres). After Governor Ramezay’s death in 1724, his widow rented the house to the government, which probably used it as secondary residence for the colony’s intendants (NOTE 2) when they were in Montreal. In 1745 the heirs sold the residence to the Compagnie des Indes occidentales (French West India Company), which was then responsible for all colonial commerce of the French empire. The Company made major renovations in 1756 – the contract stipulated that the house was to be “restored and enlarged” – that increased the size by a third. A good part of the present Château Ramezay dates from this second phase of construction under the French regime, at a time when the style of urban stone buildings stabilized in New France. The oldest parts were built in 1705. A number of other changes were made later, including the addition of secondary wings which no longer exist, and the change from a higher, steeper roof to the present one. The other change that can still be seen is the addition of an annex to which two decorative towers were added in 1902-1903, in the “chateau” style fashionable at the time, which extend the main body of the building on the east side.

The successive residents and uses of the Château Ramezay have made a great contribution to the building’s historical value. Aside from the governor of Montreal, the intendants of New France, and the English governors of Lower Canada, who all lived or worked there at different times, one should mention Benjamin Franklin. Franklin called together some French-Canadian representatives at the Château Ramezay to try to win them over to the cause of the American Revolution in 1776, when Montreal was temporarily in the hands of the Americans. The Château Ramezay and its wings also housed in turn the Montreal Court House, the Magistrate’s Court, the Ministry of Public Instruction, and the faculties of medicine and law of Université Laval in Montreal.

In the last years of the nineteenth century, the government lost interest in this building, old, worn-out and much changed by the various modifications and additions, especially since the site had become very valuable. There was a possibility that it would be sold to promoters who would demolish it and build something new. Then began the fight by the Numismatic and Archaeological Society of Montreal to save the Château Ramezay.

The fight to save the Château Ramezay

In the 1890s Montreal became a great industrial city, the economic metropolis of Canada. Its rapid growth made land in the city centre very valuable and sought-after. Promoters were full of projects, and had no interest in old buildings and nostalgic memories. Progress and profit were the new leitmotifs, as all eyes were turned toward the future. All, except those of a handful of people determined that the witness of the past and the presence of history in society should enrich culture and nourish its development.

Influential members of the Numismatic and Archaeological Society of Montreal, such as the judge and former politician Georges Baby and the businessman and amateur archaeologist William D. Lightall, were convinced that the historical value of The Château Ramezay was much greater than the monetary value of the site on which it stood. The Society proposed a plan that would showcase this unique building and fulfil the Society’s mission. It was a plan for a permanent historical museum, based on the collections gathered by members of the Society. After several months of presentations, the city of Montreal agreed to support the project, and acquired the building from the government of Quebec in 1894. It then rented it to the Society for the symbolic amount of one dollar. Finally, thanks to the hard work of Society members, the first museum devoted specifically to the history of Canada opened its doors at the Château Ramezay in 1895.

Two views of history and of heritage

At first, at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, The Château Ramezay displayed the history of the two founding peoples of Canada, French and English, a reflection of the harmonious relations within the Numismatic and Archaeological Society of Montreal, and also important First Nations figures. The view of history presented by the museum was a unifying one, centred on people who had marked the development of the country, as was usual at the time. A gallery displayed portraits of Cartier and Champlain, governor Carleton and general Grant, the great chief Tecumseh and the politician Louis Riel, complemented by objects that belonged to these great men. Thematic rooms concentrated on explorers, military men, religious orders and aboriginal peoples. The main objectives of the museum were to stimulate pride in being Canadian and to encourage the public, especially young people, to follow the edifying example of their predecessors. The Society was also ahead of its time in opening at the Château Ramezay the first public library in Montreal, thanks to the many books belonging to its members, and in creating a women’s section in 1896.

Some Society volunteers lived in the residence to develop and manage the collections, to welcome the public, to organize activities, and to lead fundraising campaigns. The money came largely from Society members and from well-off and cultured circles in Montreal. Governments, not quite convinced of the usefulness of this old building, were always hesitant to invest in it. Some benefactors of this cultural institution found inspiration abroad, especially in the United States.

The struggle by members of the Society to justify the existence of the museum and of the building continued, since it was expensive to maintain and operate. An example is the work done in 1903, which eliminated one of the functional wings added to the Château, and the construction of the decorative towers. Finally in 1929 the city of Montreal agreed to cede the building to the Society in exchange for a gift of 10,000 books from its members, a legacy which allowed the city to open Montreal’s first municipal library. Without delay, Victor Morin, then-president of the Society and also a member of the Commission des biens et monuments historiques du Québec, had the Château Ramezay classified as a national historical property to ensure its long-term preservation. It was a first for Quebec.

Until the 1970s, restoration of the building, which took place every 20 or 25 years, did not significantly change its exterior style or interior arrangement, except for the 1902-1904 work. But in 1972, as Quebec nationalism was rising and in accordance with a new style of restoration, the Château Ramezay underwent fundamental changes. For the first time, professionals took part in the work of restoration and development. The private Mcdonald Stewart Foundation invested the considerable sum of one million dollars to restore the Château Ramezay to a style mainly inspired by New France. Like Place Royale in Quebec City, which was restored at the same time, it was “redone” in the old style. The nineteenth-century interior wood panelling was eliminated. The outside was cleaned down to the stone walls, which were then covered with plaster, as in the past. The museum’s collections covering the English regime were removed, to concentrate on the French regime. The residence of governor Ramezay was reconstituted as faithfully as possible, with only two rooms kept from the time of the English governors. Finally, authentic wood panelling from the French West India Company in Nantes, France was installed in another section of the museum. Thanks to this major work and the new exhibits put in place in 1976-1977, the Château Ramezay Museum became primarily an ethnological museum, where the public could see how the inhabitants of New France and the native people lived in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Going into the twenty-first century

The year 1992 marked the end of this period of concentration on New France. To make room for a large exhibit marking the 350th anniversary of the city of Montreal, in collaboration with two other Montreal historical museums, the McCord Museum and the new Musée de la Pointe-à-Callières, the Château Ramezay once more had much of its contents removed. Three years later, on its 100th anniversary, the Château Ramezay’s mission was redefined to take into account these two important historical museums. In the end the original purpose was restored: to display its varied collections covering different times in the history of Montreal. A French-style garden replaced the asphalt parking lot in 2000.

This renewal of the museum’s original orientation reflects the evolution of the city of Montreal. Amerindians, French and English are part of the permanent display. Temporary exhibits add to the variety of periods and subjects covered, and allow the Museum to keep abreast of culture and history. Finally, multicultural programming shows the recent development of the Museum’s clientele and of Montreal’s present reality.

Martin Fournier

Historian, Ph.D.

Coordinator

Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America

NOTES

NOTE 1. There

were three governors’ positions in New France. The most important was governor

general of the colony, the direct representative of the king of France in New

France. The governor general resided in Quebec City and was responsible for

external affairs and the army. Two local governors (gouverneurs particuliers), one residing in Trois-Rivières and one

in Montreal, ensured a royal presence in the colony’s two other urban centres

(that is, service centres). These local governors were under the authority of

the governor general, but their position was still prestigious and offered

considerable powers and privileges.

NOTE 2. The intendant was the second-most important person in

the colony. Appointed by the king of France, he was responsible for managing

finances, policing (ensuring order and security), and justice in New France.

With such wide responsibilities, he sometimes had more power and authority than

the governor general.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cloutier, Nicole, « Château de Ramezay », Les chemins de la mémoire, vol. 1, préparé par la Commission des biens culturels du Québec, Publications du Québec, Québec, 1990.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Activités dans le Ja

rdin du Gouvern... -

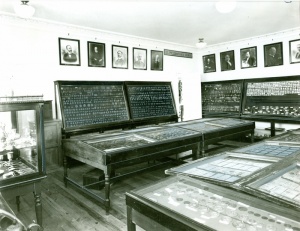

Cabinets de numismati

Cabinets de numismati

que (sans date) -

Canapé appartenant a

Canapé appartenant a

̀ Lord Sydenham... -

Carnet de bal, gala d

Carnet de bal, gala d

u centième ann...

-

Chambre d'habitant, C

Chambre d'habitant, C

hâteau Ramezay... -

Château Ramesay, Mon

Château Ramesay, Mon

tréal -

Château Ramezay et m

Château Ramezay et m

usée, rue Notr... -

Château Ramezay et m

Château Ramezay et m

usée, rue Notr...

-

Château Ramezay, Mo

Château Ramezay, Mo

ntréal -

Château Ramezay, Mon

Château Ramezay, Mon

tréal -

Château Ramezay, Mon

Château Ramezay, Mon

tréal -

Château Ramezay, Mon

Château Ramezay, Mon

tréal

-

Château Ramezay, Mon

Château Ramezay, Mon

tréal, QC, ver... -

Château Ramezay, Mon

Château Ramezay, Mon

tréal, QC, ver... -

Château Ramezay, rue

Château Ramezay, rue

Notre Dame, Mo... -

Château Ramezay, rue

Château Ramezay, rue

Notre-Dame, Mo...

-

Château Ramezay, rue

Château Ramezay, rue

Notre-Dame, Mo... -

Château Ramezay, rue

Château Ramezay, rue

Notre-Dame, Mo... -

Château Ramezay, rue

Château Ramezay, rue

Notre-Dame, Mo... -

Château Ramezay, rue

Château Ramezay, rue

Notre-Dame, Mo...

-

Cuisine du Château R

Cuisine du Château R

amezay, Montré... -

Cuisine, Musée du Ch

Cuisine, Musée du Ch

âteau Ramezay,... -

Dr Robert Wilson cost

Dr Robert Wilson cost

umé en « Samue... -

Foyer, Château Ramez

Foyer, Château Ramez

ay, Montréal, ...

-

Foyer, Château Ramez

Foyer, Château Ramez

ay, Montréal, ... -

Galerie Elgin, non da

Galerie Elgin, non da

tée -

La salle Elgin avant

La salle Elgin avant

sa restauration... -

Le canon de Louisbour

Le canon de Louisbour

g, Château Ram...

-

Le château Ramezay, s

Le château Ramezay, s

itué rue Notre-... -

Le sénateur Louis Jo

Le sénateur Louis Jo

seph Forget cos... -

Membres de la SANM, 1

Membres de la SANM, 1

894 -

MM Cole, L. A. Renaud

MM Cole, L. A. Renaud

, Tom et Mme An...

-

Musée du château Rame

Musée du château Rame

zay en 1925 -

Musée du château Rame

Musée du château Rame

zay, vers 1903... -

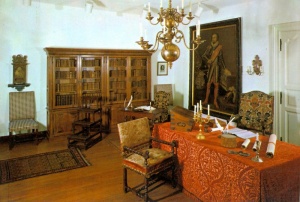

Period-room du bureau

Period-room du bureau

du gouverneur,... -

Personnages dans la g

Personnages dans la g

alerie des port...

-

Pièce de monnaie com

Pièce de monnaie com

mémorative 170... -

Pièce de monnaie com

Pièce de monnaie com

mémorative 170... -

Portail du musée en 1

Portail du musée en 1

915 -

Salle amérindienne v

Salle amérindienne v

ers 1980

-

Salle de Nantes aujou

Salle de Nantes aujou

rd’hui -

Salle du conseil du C

Salle du conseil du C

hâteau Ramezay... -

Salon, Château Ramez

Salon, Château Ramez

ay, Montréal, ... -

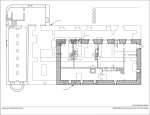

Superposition des pla

Superposition des pla

ns du Château ...

-

Timbre du musée du ch

Timbre du musée du ch

âteau Ramezay, ... -

Tramway hippomobile a

Tramway hippomobile a

u Château Rame... -

Visite guidée (salle

Visite guidée (salle

commune) en 19... -

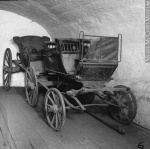

Voiture utilisée par

Voiture utilisée par

Lord Elgin exp...